America’s National Parks

Their principles, purposes, and prospects

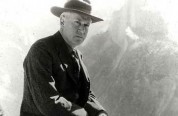

President Theodore Roosevelt and naturalist John Muir on Glacier Point, Yosemite Valley, California, 1906

Olmsted was the model of a respected establishment figure. He distinguished himself by his intellectual attainments as well as by his administrative and organizational ability. His books on the pre-Civil War South brought him early and lasting prominence. His leadership during the war, as executive secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission (predecessor of the Red Cross), together with his struggles with the Tammany mob over the management of Central Park, established him as a man of affairs. His success as a founding figure in landscape architecture gave him enormous professional stature. And, not least, his comfortable background and social standing gave him easy access to the rich and powerful.

Although Olmsted is associated with the national parks principally as a creator of ideas, he was plainly an effective shaper of events as well. He was responsible for the organization and direction of the long and difficult campaign for the establishment of a park around Niagara Falls. As early as 1869 he began meeting with influential opinion makers to plan how to combat the desecration of the falls. He directed the preparation of many magazine articles and of a petition that contained as dazzling a list of signers as any such document has ever had, including the signatures of all the sitting justices of the Supreme Court. The Niagara effort ended in success in 1883 when a bill authorizing creation of a state reservation was enacted by the New York legislature. Olmsted was plainly one kind of American hero, an idealist who could translate his ideas into effective political action.

John Muir was a very different, but at least equally appealing, figure. Muir embodied a great many of the personality characteristics of the western fantasy hero: a lonely, independent, self-reliant figure, sure of his values and uncorrupted by the softening ways of urban life. One can hardly think of the national parks without bringing to mind those photographs of John Muir, lean and austere, as unyielding in appearance as in principle, framed against the no less rugged peaks of the Sierras.

Muir was a folk-figure, but beyond that he, too, was a skillful shaper of public opinion. Unlike Olmsted, who wrote little after his early books on the South, and that with difficulty and awkward stiffness, Muir was a master of vivid, descriptive prose. He made the mountains come alive for millions to whom a voyage to California was a hoped-for, once-in-a-lifetime aspiration.

John Muir was no less impressive in person than he was in print. His landmark tour of the high country with Teddy Roosevelt, a public relations triumph of the highest order, was only one of many such experiences. Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of the influential Century magazine, describes in his autobiography an 1889 meeting with Muir and a subsequent tour of Muir country under the master’s tutelage. Thereafter, Century opened its pages to Muir, who used them to very great effect in the later battles over Yosemite.

Stephen Mather was in no sense a founder; he did not become a figure in national park history until 1915, but as the first director of the National Park Service, he dominates the whole first era of the national parks system as a governmental institution. A millionaire businessman, Mather was a disciple of John Muir and an indefatigable admirer of the Sierra Nevada mountains. And he was the very model of an American salesman. He brought to the park service the identical traits—enthusiasm, imagination, a keen public relations sense, lavish spending, and an eye for good young talent—that had made him a commercial success.

Perhaps Mather’s most characteristic, successful, and widely known achievement occurred in 1915 as part of an effort to garner support for the upcoming congressional consideration of the bill to create a National Park Service. The need for such legislation had long been recognized, for every one of the fourteen parks then in existence was being run as a separate entity. There was no central park policy or budget, and the parks, having been managed to a substantial extent by the U.S. Cavalry, were in urgent need of both money and intelligent coordination. Bills had been introduced since 1910, and Congress had held hearings twice, but no law was brought to the point of enactment until Mather came on the scene.