Facing the Past

Forensic anthropologists do facial reconstruction from remains of two crewmen found on the USS Monitor

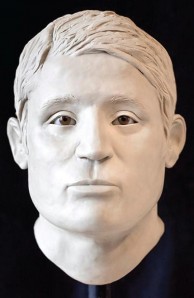

Facial reconstruction of a seaman between seventeen and twenty-four years of age, the younger of two crewmen whose skeletal remains were recovered from the USS Monitor.

Excerpted from Bone Remains: Cold Cases in Forensic Anthropology, by Mary H. Manhein. Copyright © 2013 by Mary H. Manhein. Used by arrangement with Louisiana State University Press. All rights reserved.

On December 30, 1862, the USS Monitor, an ironclad warship, was being guided to shore in turbulent seas off the coast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, when it sank beneath the waves, ending up on the ocean’s floor. Sixteen of the fifty-nine seamen on board were lost—and never found.

Commissioned in February 1862, Monitor gained notoriety for its Civil War battle with the ironclad CSS Virginia, which the South had refurbished from the USS Merrimack. The battle of ironclads began on March 9, 1862, at Hampton Roads, Virginia, and lasted for several days, with the Virginia being somewhat bested by Monitor. However, less than a year later, Mother Nature handed Monitor that devastating fate.

The Wreck of the Iron-clad “Monitor,” published in Harper’s Weekly, depicts a boat taking men off the sinking vessel, with USS Rhode Island in the background. Sixteen members of the crew were lost.

On a summer day in 2007, I met Wayne Smith, an archaeologist from Texas A&M University and a member of a special commission created in association with the USS Monitor project. Smith just happened to be in Baton Rouge to consult with Heather McKillop, one of my colleagues at Louisiana State University (LSU), about conservation of wooden artifacts she had recovered in her archaeology work in Belize. That introduction at the Forensic Anthropology and Computer Enhancement Services (FACES) Laboratory at LSU led to a collaborative research project several years later between the lab, Smith, and The Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

Monitor sits at a depth of 240 feet below the Atlantic Ocean’s surface, sixteen miles offshore from Cape Hatteras. When it sank, its most iconic feature, the armored gun turret, was displaced, ending up beneath the ship’s hull. The exact location of the Monitor has been known since 1973. However, it was not until the late 1990s that part of it was raised: the propeller and shaft. The steam engine was recovered in 2001, and in 2002, the gun turret was brought to the surface.

The revolving gun turret of USS Monitor is salvaged on August 5, 2002, off the coast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, where the ship sank during a storm on December 31,1862. Two skeletons were found preserved in the sludge that filled the turret.

(a) replica of the skull, of the younger of two crewmen, with facial tissue depth markers placed to guide soft-tissue reconstruction

Following recovery, the bones were shipped to JPAC in Hawaii—the Joint Prisoners of War, Missing in Action Accounting Command—for analysis by their forensic anthropologists. The JPAC anthropologists are charged with accounting for Americans lost in past conflicts. Their team concluded that both of the males were Caucasians (at least one and perhaps more Black seamen had been on Monitor when it sank). The anthropologists also determined that one of the two sailors was between seventeen and twenty-four years of age, and the other was somewhere between thirty and forty.

A plan began to create a documentary about Monitor and these two young men. Part of the plan would include facial reconstructions of

(b) completed 3-D clay reconstruction

Leaders in the Monitor project embraced our willingness to perform free of charge the service of recreating faces of the two men, and they made arrangements to have replicas of the skulls sent to us. Within a matter of weeks following our agreement to work on the project, a large black suitcase containing the replicas of the skull and hip bones for each of the men arrived at our lab. Upon close examination of the replicas, I concluded that I agreed with the designations of age and ancestry provided by JPAC. The older of the two individuals had grooves in his teeth where the enamel had worn down. This suggested to JPAC and to us that he might have smoked a pipe.

For the next two years, Smith and I went back and forth with the project managers, who were trying to secure a national venue for filming and promoting the project. Out of the blue, one day in early January 2012, Smith called, and he and I agreed that a summer completion date for

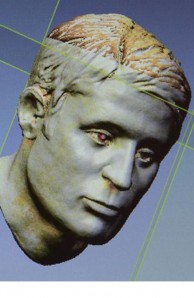

(c) computer-enhanced image

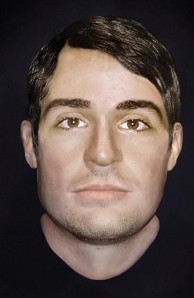

As part of the project, LSU’s University Relations Department graciously agreed to take photographs of our step-by-step process of creating three-dimensional clay facial reconstructions of the seamen. We also planned to enhance those images once they were finished, using a software program to make them appear more lifelike.

N. Eileen Barrow began the tedious process of completing the facial images. First, she cut tissue depth markers to very specific lengths for approximately thirty-two areas across the face.

(d) scan made for 3-D printing in ABS plastic

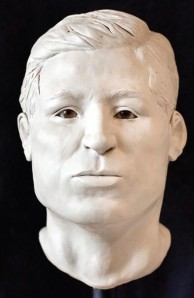

(a) completed 3-D clay facial reconstruction of the older seaman

Once all of the markers are glued in place, clay is then added to create the appearance of tissue. Some forensic sculptors add simulated muscles before placing the final finishing clay on the face’s surface; others do not. Additionally, we have formulas to re-create the nose based on the bony structure of the nose, the width of the nasal opening, and other attributes. In recreating the lips, generally speaking, one uses the distance from gumline to gumline for height of the lips, and from canine tooth to canine tooth for the width of the mouth. Prosthetic eyes are set into the skull in very specific ways that take into account the shape of the eye orbit.

Forensic sculptors who have been doing facial reconstructions for years often have formulated their own personal protocol for creating a three-dimensional image that might not always adhere to a standard

(b) computer-enhanced image, clean-shaven

Once the clay facial reconstructions were complete, Barrow took photographs of them and used Photoshop to give the men more lifelike qualities. In the case of the older seaman two images were made, one with a beard. We did not provide a beard for the younger man, after having examined quite a few historic photos that suggested a man his age might have been cleanshaven. The clay images were also scanned . That enabled us to “print” three-dimensional copies for our archives in a common thermoplastic known as ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene).

On March 6, 2012, research associate Nicole Harris, who had assisted with much of the transportation logistics and computer scanning, and I traveled to Washington for the official unveiling of the images created by our lab. The clay reconstructions had been transported to Virginia via air by UPS—their donation to the project.

One of the major reasons for creating facial reconstructions of the young

(c) computer-enhanced image, bearded

On March 8, 2013, the two Monitor sailors were laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. Researchers have no plans to raise the ship itself. Whether other sets of human skeletal remains are present in its hull may never be known. However, the vessel already has the distinction of being a formal cemetery and a final resting place of the dead, protected by federal law.

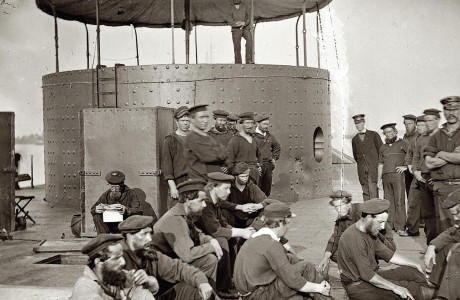

Men on the deck of USS Monitor, 1862: Based on his appearance, there is speculation that the man standing at the far right, identified as Fireman First Class Robert Williams, was the older seaman whose remains were recovered.